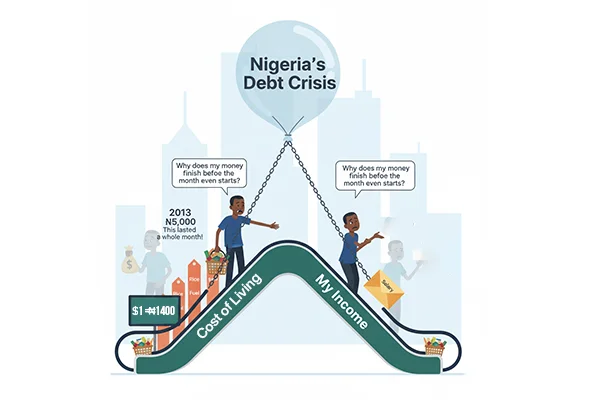

Across Nigeria today, states are borrowing more than ever, yet citizens feel poorer, services are collapsing, and salaries buy far less. Roads remain broken, hospitals lack basic supplies, schools struggle with overcrowded classrooms or poor infrastructure in most cases, and residents are asked to pay higher taxes and levies just to make ends meet. Meanwhile, many governors continue to borrow in the name of "development,” leaving ordinary people to carry the hidden cost. As national and subnational debt rises, every Nigerian has a right and a responsibility to ask their governor tough questions. Debt is not just a government statistic; it affects the price of food, transport, electricity, rent, school fees, and the security of families’ futures. When a state borrows without transparency or accountability, its people eventually pay the price.

The first question every Nigerian should ask is: How much debt does our state really owe?

Many citizens have no idea how deeply their states are in debt, partly because governments rarely disclose this information openly. Yet, this information matters. Some states owe hundreds of billions in combined domestic and external loans, and a few owe more than their annual revenue. When a state’s debt is so high that it spends most of its income repaying previous loans, it has little left for salaries, infrastructure, and social services. If your governor cannot clearly state the total debt burden and how it has changed during their tenure, that is a warning sign.

The second question is simple but crucial: What exactly was done with previous loans?

Nigerians deserve to know whether borrowed money produced real results. Did the projects promised on paper actually materialise in communities? Were the roads built, the schools upgraded, the hospitals improved, or the water systems completed? Or did the loans disappear into abandoned projects, inflated contracts, and politicians’ pockets? In many states, citizens can count the number of loans taken, but struggle to point to visible development. Debt is not inherently bad if it is used to build things that contribute to economic growth. But when governors borrow today and leave nothing to show for it, the people inherit long-term poverty and interest payments for decades.

The third question citizens should ask is: Can our state realistically repay its debt without sacrificing essential services?

A responsible borrowing plan requires a clear repayment strategy. Yet many states rely heavily on federal allocations, which fluctuate with oil prices and national policy. When revenue drops, debt repayment consumes a significant portion of the state's income. Some states already spend 30–40% of their annual allocations on debt servicing. To put this in context, international public finance standards suggest that subnational debt servicing should ideally remain below 15–20% of annual revenue (IMF Fiscal Risk Guidelines). Once a state crosses this threshold, it becomes vulnerable to fiscal stress. States spending double this benchmark are effectively entering a debt trap, borrowing more simply to repay old loans. At this point, citizens feel the consequences directly: unpaid salaries, abandoned projects, rising charges for public services, and extreme austerity.

The fourth question is critical for transparency: What are the terms of the new loans being taken?

Many Nigerians do not realise that loans differ in interest rates, repayment periods, and currency risks. Some loans are taken in dollars or other foreign currencies, which become far more expensive to repay when the naira weakens. For example: A $10 million loan costs ₦4.6 billion to repay at ₦460/$ in 2022, but costs ₦15 billion at ₦1,500/$ in 2024. This means the same loan can triple in cost simply because the naira loses value, even if the loan amount never changes. Some loans also come with high interest rates or short repayment windows that strain a state’s finances. Knowing whether a loan is concessional (cheap) or commercial (expensive) helps citizens judge whether leaders are borrowing responsibly or recklessly. A governor who cannot explain the terms of a loan does not deserve to take it on behalf of millions of citizens.

The final question every Nigerian should ask is this: How will this debt improve the lives of ordinary people?

Not in theory, but in practical, measurable outcomes. Will the loan reduce poverty? Will it create jobs, improve security, increase food supply, reduce transport costs, or make healthcare more accessible? Borrowing is only justified if it creates long-term value. If a loan cannot be traced to a clear benefit for citizens, then it is simply a burden disguised as development. Every state that borrows should be able to show how the average family will feel the difference in their daily lives.

Nigeria’s future depends on accountability. States should not borrow blindly while citizens endure rising prices, shrinking salaries, and collapsing public services. Debt can be a tool for progress, but only when managed with transparency, discipline, and honesty. Governors must justify every naira borrowed, and Nigerians must demand answers. These five questions are not just political; they are personal. Because when states borrow irresponsibly, the debt doesn’t belong to government officials. It belongs to the people.